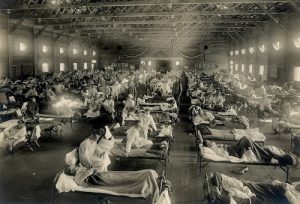

Image courtesy of the National Archives

Image courtesy of the National Archives

The Great Influenza of 1918-1919

Occurring in three distinct waves[1-4] at the tail end of World War I, the Great Influenza was the most lethal influenza pandemic in history, which, worldwide, is believed to have killed approximately 50 million people[1-3]—although estimates of numbers of victims range from 20 million to 100 million.[1,2,4] Influenza killed more people in a single year than plague did in one century during the Middle Ages.[1] The geographic origin of the 1918-1919 pandemic remains unclear—despite being popularly known as “the Spanish flu,” the first cases may well have been in the United States.[1,2,4]

One hundred years later, we are experiencing one of the most severe influenza seasons since the 2009 influenza A(H1/N1) pandemic, with record-setting hospitalizations for influenza. Although many advances in understanding, preventing, and treating influenza have taken place during the past century, we continue to be at the mercy of this potentially deadly disease. (For more information on the 2017-2018 influenza epidemic, visit Medscape’s Influenza Resource Center.)

Pathogenicity and Mortality Rates: Then

The extreme pathogenicity of the 1918-1919 virus is unmatched throughout history.[1,2] It is believed that up to one third of the world population—some 500 million people—may have been infected with that season’s influenza virus.[2] The potency of the viral strain was also unparalleled: Up to 2.5% of those who contracted the flu were killed by it,[2] approximately 5-20 times more than were expected to die.[2]

Pathogenicity and Mortality Rates: Now

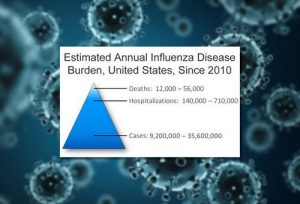

Since the pandemic of 1918-1919, the mortality rate in patients who contract influenza has been typically less than 0.1%.[2] Although the modern influenza mortality rate is dramatically lower, even in this day and age, 1 out of 1000 people who contract flu are estimated to die. Using data from six recent influenza seasons (2010-2011 through 2015-2016), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated the annual influenza disease burden for the United States, shown here.[5] To date, during the severe 2017-2018 season, CDC reports that the proportion of people seeing their healthcare providers for influenza-like illness is 7.1%, the highest since the 2009 pandemic.[6] The overall influenza hospitalization rate of 51.4 per 100,000 people in the United States, and the influenza and pneumonia mortality rate of 9.7% is also higher than average.[6]

Patients at Risk: Then

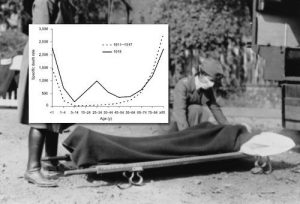

Approximately one half of those killed by the Great Influenza—contrary to other outbreaks of the flu—were young men and women in the prime of life, aged between 20 and 40 years.[1,2] Among people aged 15-34 years, the death rates from pneumonia and influenza in 1918-1919 were more than 20 times higher than during previous outbreaks,[7] as reflected by the graph of influenza deaths according to age—a distinct W-shaped curve in contrast to the typical U-shaped curve in other flu pandemics, when only the very young or very old were at risk.[2]

Patients at Risk: Now

Persons whom the CDC considers to currently be at high risk for developing flu-related complications are shown here.[8] Of interest, during the 2015-2016 flu season, older adults accounted for less than 10% of cases, but more than 60% of excess deaths from pneumonia or influenza.[9] During the current severe influenza season (2017-2018), as of February 3, a total of 63 children have died from influenza,[6] and 85% of those deaths have occurred in unvaccinated patients.[10]

Cause of Influenza: What Was Known Then

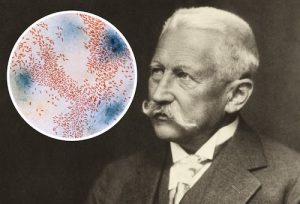

Before 1918, influenza was considered relatively unimportant—a “3-day fever,”[4] rather than a life-threatening illness. It was not on the public health radar and was not a nationally reportable illness.[1,2] At that time, the cause of influenza was misunderstood, and its links to avian and swine influenza were unknown.[1,2] Guided by the germ theory of disease, researchers believed that “Pfeiffer’s bacillus” (now known as Haemophilus influenzae), discovered by the esteemed bacteriologist Richard Pfeiffer in the 1890s, was the cause of influenza.[1,4] As the pandemic gathered steam, precious time was squandered trying to isolate this secondary pathogen and developing serums, antitoxins, and vaccines that would prove wholly ineffective. Despite obvious clinical similarities to previous outbreaks, some health professionals questioned whether the disease was in fact influenza.[2] We now know that the 1918-1919 pandemic was caused by an influenza A virus, H1N1 subtype.[11]

Cause of Influenza: What We Know Now

We now know that influenza is a highly contagious, mild to life-threatening respiratory illness that is caused by influenza virus infection of the nose; throat; and, at times, the lungs.[12,13] Flu symptoms—including sore throat, fever, weakness, fatigue, cough and respiratory symptoms, headache, myalgia, and tachycardia—usually develop within an incubation period of 2 days after exposure to the virus, although this can vary from 1 to 4 days.[12,13] Although the seasonal strains of the influenza virus are an ever-present public health concern, extremely virulent strains—such as the 1918-1919 strain—emerge periodically, for reasons that we do not fully understand. We know that influenza is common to other animal species, with certain strains (eg, avian and swine influenza) capable of zoonotic human infection.[13] One hundred years after the Great Influenza, the dominant strain causing the severe influenza season of 2017-2018 is the A/H3N2 virus.

Diagnostic Methods: Then

At the time of the 1918 outbreak, despite centuries of influenza epidemics and with limited medical understanding, diagnostic methods relied on clinical observation based on ill-defined criteria,[1,2] which included the presence of fever, chills, weakness, vomiting, and respiratory distress, along with generalized body aches, earaches, and headaches.[4] Some patients experienced hemorrhaging, mental changes, and eventually cyanosis.[1] Influenza was often misdiagnosed as dengue, malaria, cholera, dysentery, or typhoid, because the patients’ severe symptoms did not seem to fit with what doctors had experienced with influenza.[1]

Diagnostic Methods: Now

The diagnosis of influenza still relies in part on defined clinical observations, but laboratory tests—such as rapid influenza diagnostic tests and rapid molecular assays—using a viral culture of throat, nasal, or nasopharyngeal samples are now commonly used to confirm influenza. These diagnostic methods tend to provide high specificity but only moderate sensitivity.[12] Depending on the strain, they can fail to identify the virus. Rapid tests can also be less effective in adults than in children.[14] Of interest, to date in the 2017-2018 influenza season, 26.1% of respiratory specimens have tested positive for influenza.[6]

Propagation of Influenza: What Was Known Then

Without fully understanding the underlying reasons, at the time of the outbreak, healthcare workers knew that influenza spread from person to person after an incubation period of 3-6 days and that it could spread by hand to mouth or nose and then by hand to an infected object.[1] It was also known to be an exceptionally contagious disease, aggravated by crowded conditions, such as the army barracks and centers for displaced people that were typical at the end of World War I. Such signs as this one, with the dramatic slogan “Spit Spreads Death,” were posted to remind the public that the oral secretions of someone with the flu could infect another person. Anyone caught spitting was arrested or fined.

Propagation of Influenza: What We Know Now

It is now commonly accepted that the influenza virus spreads when infected people expel droplets (which can travel up to 6 feet) while talking, coughing, or sneezing, and that the virus can in some cases spread from person to object to person.[15] For this reason, in addition to covering nose and throat when coughing or sneezing, frequent handwashing is advised to reduce influenza transmission. According to the CDC, healthy adults can shed the virus 1 day before symptoms of the flu are present and up to 7 days after falling sick.[13] Children can transmit the virus for a longer period.[15] We also know that some infected persons do not display any clinical symptoms of the flu.[15]

Treatment Options: Then

Doctors were by and large caught empty-handed when influenza struck in 1918. Despite intense and diverse efforts—which included bleeding, cupping, purgatives, cardiac stimulants, and many more outlandish treatments—medicine was essentially powerless to alter the course of the pandemic.[2-4] The public turned to such fraudulent remedies as camphor, garlic, and gargling with disinfectant.[1] Physicians could relieve some flu symptoms and suffering with aspirin, oxygen, and morphine, but otherwise watched helplessly as countless young, healthy patients succumbed to the disease. William Welch, the well-known pathologist, said at the time that the pandemic would “forever be a great shadow cast upon the medical profession.”[16]

Treatment Options: Now

The advent of antiviral drugs, which first became available in the mid-1960s,[17] has helped change the landscape for the treatment of influenza, although these agents cannot be considered panaceas. A recent systematic review concluded that neuraminidase treatment is likely to be effective at reducing mortality among hospitalized patients, and symptom duration by up to 1 day in the general population.[18] Oseltamivir or zanamivir prophylaxis is likely to be effective at reducing secondary symptomatic influenza transmission.[18] These agents work best when started within 2 days of symptom onset, when they may prevent serious complications from influenza, such as pneumonia.[19]

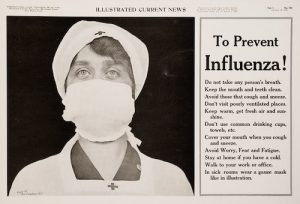

Preventive Measures: Then

In 1918-1919, in the absence of treatment options, it became increasingly clear that avoiding exposure to sick people was the only way to prevent illness. Because total physical isolation was not practical for all, realistic preventive measures were advocated, such as those enumerated in this 1918 advertisement.[20] Public gatherings were banned, and paper cups even came into use to prevent contamination of common drinking cups.[1] The mandatory face masks that were widely distributed to the public became the symbol of the flu epidemic.[1] However, these gauze masks, despite being considered “lifesaving measures,” were in all likelihood useless in preventing transmission of the virus.

Preventive Measures: Then

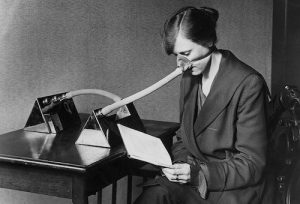

This image of an office worker in 1919 wearing a “flu nozzle” illustrates the extent to which even young, healthy people went to avoid getting the flu during the great epidemic. Young adults had reason to be fearful: The mortality rate was highest in 25- to 29-year-olds. The reason that healthy people in their mid- to late 20s were at higher risk was unknown at the time, but recent speculation has centered on the possibility that unlike younger and older cohorts, this particular cohort had not been exposed to the same influenza viruses as children, and therefore hadn’t developed antibodies. The theory argues that childhood exposure of various age cohorts to different pandemic viruses was a key factor underlying the age-specific patterns of fatality observed in 1918.[21]

Preventive Measures: Now

Influenza vaccination is complemented by “everyday preventive actions,” many of which mirror those advocated in 1918-1919: avoiding close contact with sick people, covering the nose and mouth with a tissue when coughing or sneezing, staying home if you are sick, and maintaining good general health practices. Frequent handwashing with soap and water or hand sanitizer, now considered a critical preventive measure, was not emphasized during the great epidemic. And it still isn’t known whether the modern equivalent of the gauze mask—the disposable facemask—effectively protects against influenza. Twenty-first century preventive measures also encompass a sophisticated global network of surveillance, monitoring, and reporting, such as FluView and FluView Interactive, operated by CDC’s Epidemiology and Prevention Branch and the World Health Organization’s Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System

Influenza Vaccines: Then

In 1918, scientists already understood the concept of vaccines, but an effective influenza vaccine remained elusive because they were unable to isolate the true etiologic agent. That didn’t stop them from trying, however. Multiple vaccines, antitoxins, and antisera were developed, primarily aimed at Bacillus influenzae or various strains of pneumococci, despite the suspicion harbored by some that influenza was caused by a filterable virus.[1] Some of these “vaccines” were administered to patients in a desperate attempt to save lives; others were administered to the public or members of the military.[1] None were effective against influenza, either prophylactically or therapeutically.

Influenza Vaccines: Now

With the Great Influenza still in the rearview mirror and another flu epidemic under way, scientists in 1933 finally achieved what they had failed to do in 1918-1919—isolation of the what proved to be the influenza A virus.[22,23] By the end of World War II, a bivalent influenza vaccine had been successfully used to prevent flu in US troops, and vaccination of civilians began.[23] This led to the discovery that the antigenic composition of the seasonal influenza virus can change. Today, vaccine composition is adapted annually to match circulating viral strains as closely as possible.[23] A yearly flu vaccine is considered the most effective way to prevent influenza,[24] despite the virus’s propensity to mutate, rendering the vaccine less effective during some flu seasons than others. The next frontier in influenza vaccination may be the “universal vaccine,” which can protect against all types of flu with a single dose.[25]

Attitudes Toward Influenza: Then

In this photograph, a streetcar conductor denies boarding to a passenger who isn’t wearing a mask. At the time of the first outbreak, the public’s attention was riveted on World War I. Despite previous epidemics—including the “Russian flu” some 30 years earlier—influenza was not a major public health concern, but attitudes changed dramatically as the potency of the second wave became apparent and the dead began, literally, to pile up. Panic set in when the public realized that medical science was unable to protect them and as healthcare workers were seen to die at the same rate as their patients. Fear of contracting the flu caused work absentee rates to spike[1] and made people unwilling to help one another. Government attempts to boost morale with such messages as “There is no cause for alarm!” and “Don’t get scared!” had the opposite effect, to no one’s surprise.[1] Once the pandemic had run its course, people were anxious to bury the memory, perhaps associating it with a war that they wished to forget.[4]

Attitudes Toward Influenza: Now

The Great Influenza of 1918-1919, and the fear and panic it engendered, have been consigned to the history books. Attitudes toward influenza have evolved over the past century. The data would lead us to believe that only about one half of the US population now consider the threat of flu serious enough to take the preventive step of vaccination. During the 2015-2016 flu season, vaccination coverage was 45.6% among those aged 6 months or older.[26] Adults older than 65 years—who are typically more vulnerable—take the threat more seriously, as reflected in a vaccination rate of 63.4% during the same season.

A nationally representative survey[27] found that among adults, the leading reasons for skipping the vaccine were a lack of perceived need (28%), “not getting around to it” (16%), “not believing in flu vaccines” (14%), and the perceived risk for illness or side effects from vaccination (14%).

Still, the public’s reaction to the H1N1 pandemic of 2009 illustrates the potential for influenza to trigger widespread alarm. With all of the headlines about the severity of the current 2017-2018 season—hospitals at the breaking point, antiviral shortages, school closures, and rising deaths from influenza—the public’s attitude toward influenza may evolve further.

Steven Rourke | February 9, 2018 | Contributor Information

Medscape > Medical News & Perspectives