The NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL of MEDICINE

Eduardo Bruera, M.D.

The opioid-overdose epidemic now causes more than 30,000 deaths per year in the United States. In response to the increasing death toll, many measures have recently been implemented, including reclassification of hydrocodone as a Schedule II opioid and new requirements for physician review of prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) databases in most states. Guidelines for opioid prescribing have been issued by multiple organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),1 and the Surgeon General sent a letter with recommendations to all U.S. physicians. These and other educational and regulatory measures have resulted in a reduction in the quantity of opioids prescribed,2 but there have been unintended consequences.

Although guidelines from most organizations, such as the CDC, exempt patients with cancer-related pain, the median daily equivalent opioid dose of morphine prescribed by cancer specialists before referral of patients to supportive and palliative care programs decreased from 78 mg per day in 2010 to 40 mg per day in 2015.3 The types of opioids being prescribed have also changed, with a significant decrease in the use of Schedule II opioids such as hydrocodone and transdermal fentanyl and an increase in the use of Schedule IV opioids such as tramadol.3

These findings are not surprising. Physicians already burdened by frequent and time-consuming denials of payment and preauthorization requirements for opioids from insurers now face the extra burdens of universal screening of patients for risk for nonmedical use of opioids, PDMP database review, more frequent monitoring of opioid use, and sometimes ordering and interpreting of urinary opioid screening tests. Many have opted to use nonopioid agents or Schedule IV opioids, or to refer patients requiring opioids to palliative care or pain specialists.

Against this worrisome background, on February 8, 2018, our cancer-center pharmacy announced that there were severe and immediate shortages of the three most commonly used parenteral opioids: morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl. Similar shortages were reported in the vast majority of cancer centers and hospitals in the United States.4

These shortages resulted from a series of events related to the tightening of government regulations and controls in response to the opioid-overdose epidemic, such as a Drug Enforcement Administration proposal to reduce opioid manufacturing for 2018 by 20%, as well as manufacturing problems in several pharmaceutical companies, including violations in manufacturing practices discovered by the Food and Drug Administration.4 The opioid shortage is not expected to be resolved in the near future, so hospitals will need to implement mitigation strategies.4

The shortage has serious consequences for patients and physicians. Parenteral opioids provide fast and reliable analgesia for patients admitted to the hospital with poorly controlled pain, patients who have undergone painful procedures such as major surgery, and those who were previously on oral opioid regimens but are unable to continue treatment by mouth. Shortages of the three best-known parenteral opioids may increase the risk for medication errors when it becomes necessary to switch a patient to a less familiar drug or to use opioid-sparing drug combinations. Opioids are already among the drugs most frequently involved in medication errors in hospitals. There are also increased risks of delayed time to analgesia and of side effects resulting in unnecessary patient suffering and delayed hospital discharge.

Physicians’ burden and stress increase when they are forced to make sudden changes in practice. Pharmacies currently send regular e-mail updates notifying prescribers about which of the three parenteral opioids are or will be unavailable over the next few days. Even for those of us who prescribe opioids daily, it is hard to read and remember all these e-mails. Usually, after a physician orders parenteral opioids (sometimes hours later), the pharmacy will notify the physician that the requested opioid is not available. The physician must then access the patient’s medical record, calculate the opioid dose ratio and adjustments for switching to an alternative opioid, try to notify the patient, and write new orders. This process is time consuming and stressful and will further discourage physicians other than palliative care and pain specialists from prescribing opioids.

Most hospitalized patients and almost all patients with cancer need opioids, either on a temporary basis after surgery or painful treatments such as stem-cell transplantation, or longer for cancer-related pain or dyspnea. It is impossible to appropriately treat such a large number of patients unless most physicians are able and willing to prescribe opioids. There were not enough palliative care and pain specialists to meet patient needs before the shortages began, and universal referral of patients who need parenteral opioids will therefore only result in more undertreated pain.

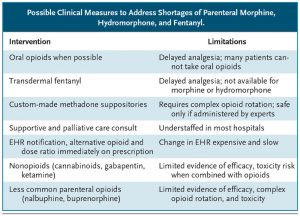

Possible Clinical Measures to Address Shortages of Parenteral Morphine, Hydromorphone, and Fentanyl.

There are some possible clinical alternatives. A series of measures to address the consequences of the opioid shortage for patient care are summarized in the table. The electronic health record (EHR) might help by notifying physicians immediately when the opioid is in shortage and providing information on alternative available opioids and the recommended dose ratio. But all these proposed measures will, at best, be only partially effective in achieving analgesia, and some will result in increased complexity of care and physician burden.

What U.S. patients need is access to parenteral morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl. These opioids are 80 to 220 years old, are inexpensive, and can be manufactured with minimal technology. Perhaps for these reasons they are unattractive to manufacturers.

What are some longer-term solutions? The dependence on unreliable manufacturers and an unreliable regulatory environment compromise patients’ access to parenteral opioids. Like the strategic oil reserve designed to maintain a national supply, a strategic opioid reserve in all hospital pharmacies and health networks could mitigate the impact of similar episodes in the future.

With minimal regulatory changes, pharmacies in most health care facilities could successfully prepare parenteral opioids from powder. Some midsize Canadian hospitals have successfully prepared solutions of most opioids for decades, at much lower cost than buying them from drug companies.5

Unfortunately, the leaders of universities and funding agencies have largely failed to establish and support academic structures aimed at alleviating pain and suffering. Well-supported teams of clinical and translational researchers will probably ultimately discover better pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic therapies to replace centuries-old opioids. Until they do so, however, we can make it a clinical and ethical priority to secure the availability of parenteral opioids for U.S. patients who are in pain.

This article was published on July 18, 2018, at NEJM.org.